Why have midwives been linked to witches in European history?

by Helen King and Tania McIntosh

What is your image of the midwife? For many people today, it’s the one we see in the long-running BBC drama Call the Midwife, about to enter its seventh series. This drama began as a fictional reworking of the autobiography of a real midwife, Jennifer Worth, who worked in the East End in the 1950s. Its storylines are sometimes complex and not always happy or easy. But the midwife comes across as a strong, warm, brave, knowledgeable and caring woman willing to sacrifice her time and energy in the service of mothers and babies. The setting is domestic, and the midwife presented as a saviour – sometimes literally.

Behind this image, a less friendly version of the midwife still lurks even today: cruel, ignorant and self-serving. This perception does not come from Call the Midwife or from contemporary fly-on-the-wall drama documentaries like One Born Every Minute. Instead it reflects investigations carried out into hospital cases and practices, which have led to high-profile government pronouncements about midwifery, consumer campaigns and media fascination with individual tragedies.

A 2015 UK official report investigated a cluster of baby deaths and a maternal death at Morecambe Bay NHS Trust between 2004 and 2013. The Royal College of Midwives acknowledged these events as ‘a drawn-out and tragic failure in U.K. maternity services’. The report did not pull its punches in portraying midwives and midwifery care. A group of midwives called themselves the ‘musketeers’ because of their ‘one for all’ approach which pursued ‘normal birth’ regardless of what was best in an individual case.

Enter the historian

For a historian, there’s something very familiar about these recent news stories in which midwives are presented as powerful, dangerous, and pursuing their own model of ‘normal birth’.

Even in the early 1960s, the period of Call the Midwife, an article was published by an obstetrician exploring ‘human factors’ in maternity care. The article used the testimony of women to describe a system that left them feeling ‘loneliness, indignity and despair’. One woman said of midwives ‘there seems to be nothing human in them at times.’ It was not suggested that midwives were dangerous, but that they were cruel.

Going back to the Victorian period, doctors increasingly wanted to be involved in caring for women at birth. This made them professional rivals to midwives, and they often played dirty by describing midwives as dangerous and ignorant. Doctors managed to paint themselves as educated and safe, even at a time when neither of these things was true in relation to birth. As late as the 1930s women cared for in labour by General Practitioner doctors were more likely to die than those attended by a midwife. Poor working relationships between midwives, obstetricians and paediatricians played a part in the Morecambe Bay tragedy. The report spoke of a ‘them and us’ culture and poor communication hampered clinical care.

There have been claims by twentieth century historians that midwives working in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were frequently prosecuted for witchcraft. Back in 1990, historian David Harley published an article on ‘Historians as demonologists: the myth of the midwife-witch’ in which he exposed this as a ‘powerful myth’. He found just one English trial in which a midwife was even accused: a Mrs Pepper. She was accused not because of anything related to midwifery, but for giving magical remedies to a sick man. This isn’t surprising, because in early modern Europe what mattered in choosing a midwife was her reputation as a reliable and respectable member of her community. Harley looked into the possibility that deaths in childbirth or still births, led to popular suspicion of the midwife. He showed that the myth of the midwife-witch was just a literary convention with no basis in reality. It didn’t even affect people’s attitudes to the real midwives who helped them in birthing.

So the mixed message of the midwife as both angel and demon is not new. Childbirth is a unique, personal and animal experience. Midwifery has always been viewed as complex, and its practitioners as having the potential to be cruel and dangerous as well as kind and caring. Perhaps midwives came under suspicion because childbirth was seen as dangerous. Stillbirths have always happened and perhaps we may need someone to blame.

There’s also a gender dimension. It’s unusual for women to be in control of a life and death situation. Individual and family happiness, even whole dynasties, depended on what happened at birth.

Today as in the past, midwives continue to take the blame for uncertainty; for the times that good outcomes can’t be guaranteed. It’s hardly surprising that society had strong views about what a midwife should be like, and fears about what she might be like.

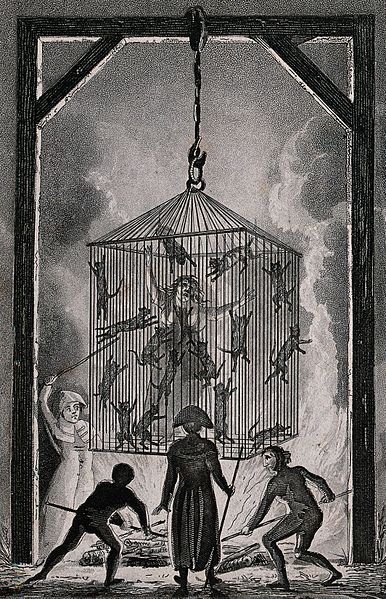

Image information: Aquatint depicting the burning of French midwife Louisa Mabree. The black cats in the cage are suggestive of witchcraft. (Courtesy of Wellcome Images.)